Doomocracy: Hip Hop’s Disco Phase

I grew up in the era of grunge. I still remember the first time I saw 1,000 kids going nuts to “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. It was an under twenty-one club in Quebec during the winter carnival. I was seventeen and half drunk on the mixture of red wine and grain alcohol they called caribou. It was the first time I realized that there was a spirit to an age. I had always read authors who insisted on what I thought was a gross oversimplification; now I am one of them. There are key moments when the music, sometimes a specific song, acts as the most perfect and concise description of the collective consciousness. We are not in such a moment. We are living through the era of Hip Hop disco, the awkward adolescence of this art form.

I grew up in the era of grunge. I still remember the first time I saw 1,000 kids going nuts to “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. It was an under twenty-one club in Quebec during the winter carnival. I was seventeen and half drunk on the mixture of red wine and grain alcohol they called caribou. It was the first time I realized that there was a spirit to an age. I had always read authors who insisted on what I thought was a gross oversimplification; now I am one of them. There are key moments when the music, sometimes a specific song, acts as the most perfect and concise description of the collective consciousness. We are not in such a moment. We are living through the era of Hip Hop disco, the awkward adolescence of this art form.

Browse the charts, or better, tune in Top 40 radio, and you will find that Taio Cruz “came to dance, dance, dance, dance,” that Enrique Iglesias and Pitbull like “the way you move on the floor,” that Usher admits the “DJ Got Us Fallin’ In Love.” As a phenomenon, this music is neither very interesting nor particularly relevant. I never thought Hip Hop, a form that is laudable in many respects would look to or indulge in disco, a style that is looked back on with almost universal derision.

The problem, just as it was in the 70s, is the site of the music. The 70s saw the site of music swing towards its extremes. On the one hand, it located itself in the garage. The children of the first generation born into Rock & Roll took their second hand instruments and their worn down ideas of music and turned them into something in which the rawness, like a fresh wound, was the source of inspiration and innovation. The question was: could a poor kid from nowhere make a noise ugly enough that when he tried to out-scream it, an audience could find its own blunted catharsis? On the other hand, there was the music industry, which had finally come to terms with its role as a behemoth decider of culture, alongside movies and television. This music was born in the studio and destined for the nightclub; from all sides, you had to pay to play. Artists compromised. Producers closed ranks. The velvet rope became a part of the public consciousness, and the music became a lesson in disconnectedness. Patti LaBelle asked 1,000 sweaty scene-sters if they would like to sleep with her tonight.

The amazing thing about Hip Hop is that these two forces are not opposed as they were in the 70s. They now form a continuity. The music that started in the ghetto, on the street corners and in the Friday-night house parties has become very nearly its opposite. I wonder if Run DMC would recognize Lil’ Wayne. In Run DMC’s first effort, on a track called “Sucker MCs,” they found their baseline in “Live at the Disco Fever” by Luvbug Starski. Starski, a master appropriator, stages his homage to another street-corner form, Doo-Wop, in the legendary South Bronx club whose name, inspired by Saturday Night Fever, would later be appropriated less sensitively by bad movies and even worse compilers. It would seem that Run-DMC were post disco, and pro Disco Fever (the club).

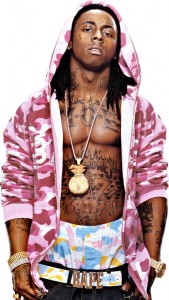

The difference is subtle but significant. Disco Fever was one of the first times that the music, Hip Hop, had ever been enfranchised, brought indoors, sheltered and appreciated. Run DMC, through Starski, are acknowledging a moment of creation in the midst of a moment of creation, their first album. The early history of Hip Hop is filled with these kind of doublings and homages, creating a web of meaningful interconnections. Lil’ Wayne, in the title track of his recent, Right Above It, creates a link to the ghetto as well, with very different results. Wayne’s ghetto is the one found in the movie Slumdog Millionaire, the one viewed from air-conditioned comfort in the midst of Dolby Surround Sound, the one that isolates him from sweat and desperation. He is on the less interesting side of the velvet rope, in the rarefied environment of new money millionaires. In one of his biggest hits to date, a collaboration with Fat Joe, Wayne makes “it rain on them hos.” The rain here is $100 bills. The locale is the photo studio, and Wayne sits atop a shipping pallet of the bills, while his hos dance near him, but importantly, never in physical contact. He touches the bills, the bills touch the girls, and this is some kind of bizarre completion of a sexual act. Am I wrong to think of Patti LaBelle, singing in French to the patrons of Studio 54?

It would be tempting to trace this transition from lo-fi to hi-fi, from street corner to studio, from tape sold from a car’s trunk to celo-wrapped disc. It would be tempting to locate the exact moment when Hip Hop changed, but it is more important to know that it did, and to try to understand it now that it has. It would be easy, and wrong, to write it off as a wrong turn, a branch of evolution that has little potential. Just as people who wish it were so believe that disco died along with the club and drug scenes that supported it, it would be small-headed and unfairly biased. Disco changed; it shed its most cliché markers and carried on, eventually becoming the hair bands of the 80s, the rave scene of the 90s, and so on. You can still find it today, if you know where to look. So, what then for Hip Hop?

Hip Hop is in its adolescence, and disco may be considered youthful indiscretion, but I prefer to think of it as an awkward stage. There is a part of pop music that will always be about fantasy wish fulfillment. Travie McCoy is making big numbers with “I wanna be a Billionaire.” Likewise, this club-centered site for Hip Hop is presenting an aspiration for the vast majority of its audience. Many people who could never afford to own a “409” still happily sang along with The Beach Boys from the back seats of their parent’s grocery getters. Who doesn’t want to be a big shot with access to the VIP and the ability to “drop stacks” on any frivolity? Hip Hop will eventually outgrow these dreams. Do you remember when the urban streets looked more like a yacht club than most actual yacht clubs? How about when Hip Hop stars dressed and sang about brands that would embarrass the most oblivious Euro-trash? In a few years, we will look back and wonder if the club scene was really that good at the beginning of the century. By that time, Kanye West will be safely contained as a national treasure, and a new generation of artists will be singing about a new generation of things to want. It is most likely that the club will be displaced as the site of the music.

This would tend to minimize the importance of the culture at this moment, but I would like to suggest that it is something more significant than just fantasy wish fulfillment. Hip Hop is big. It has achieved a centrality that is impossible to ignore. In some ways, the music is a celebration of this fact. Many genres celebrate the icon of the working class hero, the struggle to the next rung of the ladder. What happens when you hit the top, when your Hip Hop star is a legitimate mogul? industrialist? venture capitalist? What happens when they are the owners? While Lil’ Wayne is presenting an aspiration, he is also celebrating an achievement, and while Run DMC might not celebrate the content of the message, they would never minimize the achievement. Moving from the street corner to the penthouse is no small feat.

From this perspective, the club is a special place. It is a zone where the once dominant culture has been displaced entirely. It is a microcosm where the ladder is complete from top to bottom and upward mobility is not a concept but an established fact. There is a democracy to the club, once you make it past the velvet rope, and so it is a model for a worldview. We learn by seeing, and in the club, you can see the top, and you can see that they are not so different from us, the sweaty hordes. It sounds like a small thing, but it is the small thing that leads to big things. Who will be better served: the kid who listened to Run DMC’s “My Adidas” and understood something about authenticity or the kid who listens to Lil’ Wayne’s “A Milli” and sees a path to becoming a “young money millionaire.”

Hip Hop’s disco phase may be a hard one to embrace wholeheartedly, but you would do well not to ignore or avoid it. It is easily as important as the Obama presidency. Pop music tells us something important about ourselves. Are we reliving the 70s? Clearly, some of us are.

Songs Cited

Cruz, Taio. “Dynamite.” Rokstarr. Prod. Benny Blanco Dr. Luke. Island, 2009.

Iglesias, Enrique. “I Like it.” I Like It. Prod. RedOne. Universal Republic, 2010.

Joe, Fat. “Make it Rain.” Me, Myself & I. Prod. Scott Storch. Terror Squad, 2006.

LaBelle. “Lady Marmalade.” Nightbirds. Prod. Vicki Wickham Allen Toussaint. Epic, 1974.

McCoy, Travie. “Billionaire.” Lazarus. Prod. The Smeezingtons. Fueled by Ramen, 2010.

Nirvana. “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Nevermind. Prod. Butch Vig. Van Nuys: DGC, 1991.

Run DMC. “My Adidas.” Raising Hell. Prod. Russell Simmons Rick Rubin. Profile Records, 1986.

Run DMC. “Sucker MC’s.” Run DMC. Prod. Russell Simmons. Profile/Arista Records, 1984.

Starski, Luvbug. “Live at the Disco Fever.” Live at the Disco Fever. Fever Records, 1986.

The Beach Boys. “409.” Surfin’ Safari. Prod. Murry Wilson. Capitol Records, 1962.

Usher. “DJ Got Us Fallin in Love.” DJ Got Us Fallin in Love. Prod. Shellback Max Martin. LaFace, 2010.

Wayne, Lil’. “Right Above It.” Right Above It. Prod. Kane Beatz. Young Money, Cash Money, Universal Motown, 2010.

Wayne, Lil’. “A Milli.” Tha Carter 3. Prod. Bangladesh, Cash Money, Universal Motown, 2008.

Genial post and this enter helped me alot in my college assignement. Gratefulness you seeking your information.